Artificial Intelligence, citizen science and the democratization of science

Simona Cerrato

April 7, 2022, 4 p.m.

Marisa Ponti, Professor in the Division of Learning, Communication and IT, in the Department of Applied Information Technology, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, recently published “Human-machine-learning integration and task allocation in citizen science” (Humanities and Social Sciences Communication, 9 February 2022), together with Alena Seredko. The study analyzed and explored the complex and challenging area of human-machine learning integration in citizen science projects.

I find it very interesting that you are a hybrid of sociologist and information scientist: contemporary science is indeed transdisciplinary, often uncertain and ambiguous and cannot do without the contribution of social sciences and humanities. Can you tell me something more about how you combine, in your research, these two fields?

There is an easy answer to this question. I place myself in a field called social informatics, namely the study of information and communication technology in culture and institutional contexts. It examines technology from an interdisciplinary perspective and analyses the uses and consequences of technology that take into account its interactions with institutional and social contexts. This is what I do.

I also draw from Science and Technology Studies, another large scholarly area that examines the consequences of science and technology in historical, cultural, and social contexts. This huge area of research encompasses a very broad range of perspectives, fields, history of science and technology, sustainability studies, infrastructure and policy studies, philosophy, sociology just to mention a few.

The high interest in these fields is driven by the fact that many issues in contemporary science and technology are now multidimensional and need to be considered from different perspectives. This is especially true when you study the use of technology.

Your recent publications focus on Artificial Intelligence…

Yes, in particular on the use of machine learning which is a subset of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that brings enormous attention not only from scholars. Indeed, it is crucial that people pay attention to artificial intelligence since it will occupy the majority of our lives, social realms, and personal relationships, and we will be influenced and affected by AI to an increasing degree.

We are already! even though we are not aware of its presence in our daily life. It just creeps into our life in ways we don’t control, making a lot of things easier, without us being aware of it.

Yes, I think so… There should be some kind of general literacy on AI. If you want to start learning something more about AI and its presence in our lives, have a look at this wonderful course called We are AI: Taking control of technology (https://dataresponsibly.github.io/we-are-ai/) created by the Center for Responsible AI (R/AI) at the New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering, in collaboration with the P2P University, and the Queens Public Library, which provides a new understanding of artificial intelligence and its impact on daily life.

And how can citizen science fit in this context? What is the role played by machine learning in citizen science projects?

Many citizen science projects have designed complex human-machine systems to take advantage of the strengths of both. GalaxyZoo, for example, combines both machine efficiency and speed with the human ability to recognize shapes to classify huge amounts of galaxies. This model is very common: we turn to machines when we have too much data to classify or too many images to annotate, and not enough people to do the job.

Even so, when we add machine learning to the equation, we are faced with the question: Who or what is doing what? This is called functional allocation (also called task allocation). The question is not trivial and has a lot of implications. The philosopher Bruno Latour taught us that machines are not just passive tools; they have agency, they resist, and they can have consequences on our actions. If you place technology within a context to carry out certain tasks, the technology does not just remain inert.

Technology is not neutral…

It is not neutral, inert, or passive.

The distribution of tasks among humans and machines has always been a crucial part of human-machine interaction research, which includes cognitive engineering, human factors, and human-computer interaction. This remains an important research area even today. In the early fifties of the twentieth century, Paul Fitts introduced the famous HumanAreBetterAt (HABA) and MachineAreBetterAt (MABA) lists. This states that machines are good at repetitive tasks and less good at ambiguous tasks, while humans are better at creative tasks.

Fitt’s list has been very influential but also criticized. After all, it comes “natural” to assign something tedious, time-consuming, and boring to machines and keep for humans the more creative tasks or tasks that machines are said not to be good at, such as identifying shapes, as in the Galaxy Zoo project.

But machines are becoming better very quickly…

Yes, indeed. That's the problem with Fitt's list: these attributes are kept stable, and are part of "the way people are," as well as "the way machines are.". It does not take into consideration that cognitive work is going to shift as machines are becoming better in many areas, even in identifying outliers. The list of tasks that machines can do is growing: machines’ abilities are not remaining at the same level forever. At present, algorithms are still second to humans at doing certain things, but this is changing. Thus, we must think about what we will do and what machines will do.

Currently, the primary concern of researchers in the classification projects I examined in another study is how to distribute tasks between humans and machines as efficiently as possible. The goal is to maximize efficiency and speed. All the narratives I examined had this goal in common.

This theme places us in front of many ethical questions, regarding inclusion, equal opportunities for all and possible consequent discrimination towards fractions of society that are already underserved. From your point of view, how can we deal with them?

I think a question we should ask ourselves is: when we combine artificial intelligence with citizen science, do we aim to maximize productivity at the expense of democratizing science? I don't have a final answer. Some people might argue that they are not mutually exclusive, and they could have a point there. It is however not a neutral choice, since if you choose either way there are consequences.

There are two ideal types regarding the nature and goals of Citizen Science. While one main tradition of Citizen Science focuses on scientific outputs through activities such as data collection and environmental monitoring (I am referring to Rick Bonney), the second tradition focuses on opportunities to make science more responsive to the needs of citizens and to include their local knowledge and personal experience (I am referring to Alan Irwin). The productivity view and the democratization view have different focuses. Definitely. Productivity focuses on numbers, measures, key performance indicators, to use a term dear to the EU Commission. Democratization emphasizes the diversity of participants, which means that it is not confined to the usual group of men, whites, educated people who live in the West.

This is the usual problem of representation of diversity in the public context, and the figure by Fitts represents a man, a typical white, educated man.

Yes, true! And after seventy years, here we are, still discussing diversity.

By democratizing science, we aim to align it more closely with the public interest. Therefore, we think about science not just as something for scientists. Taking the shape of galaxies as an example, this is a topic that most people don't even know about (this does not mean that the topic is not relevant per se!), I am fairly certain that most citizens are more concerned with the consequences of having heavily polluting companies nearby or noise that causes health problems. Bringing science more in line with the public's interests is also part of a new vision for science and the role of the public in it.

Do you have a solution? or at least some recommendation?

I don't have a solution or empirical data: I just raise some concerns that should be verified. As a first concern, we might fear that AI will reinforce some biases, including gender and racial biases, reducing the diversity and quality of the solutions that can be achieved. As an example, take the official taxonomy used as the golden standard by Western scientists to classify genus of plants or animal species. How about indigenous knowledge? Those who study biodiversity in the Amazon or in other parts of South America, Africa, and Asia have discovered that indigenous people have their own taxonomy, which is neither used in science nor when we apply artificial intelligence or machine learning.

The second concern is working with opaque algorithm systems that most people are unaware of. They don't even know how these systems learn, how they are trained, and in general how they work.

We organized a Citizen science, AI and algorithms panel at the third ECSA conference in 2020 to initiate a dialogue on how citizen science collaborates with algorithms. Several issues came up that we can group into four main topics: 1) democracy and participation, 2) skilled biased technological change, 3) data ownership versus public domain, 4) transparency, which has to do with the opaque functioning of these systems.

In skilled biased technological change, we are likely to require new skills every time we change a technology to perform a job or a task. It may be that we are lowering the need for certain skills or increasing the need for more sophisticated skills. When we use machine learning, it has been observed that machines become more and more accurate at categorizing. If, in the future, humans no longer need to use their classification skills, for example, to recognize species, they should shift to some other tasks, for example, focusing on identifying outliers or validating what machines do, or for more imaginative and more creative tasks. To accomplish these tasks, we may need people with higher-order skills. As a result, one of the risks is that participant diversity will decrease even more because we will be able to draw from a much smaller pool of people.

Can you give a concrete example from your recent study?

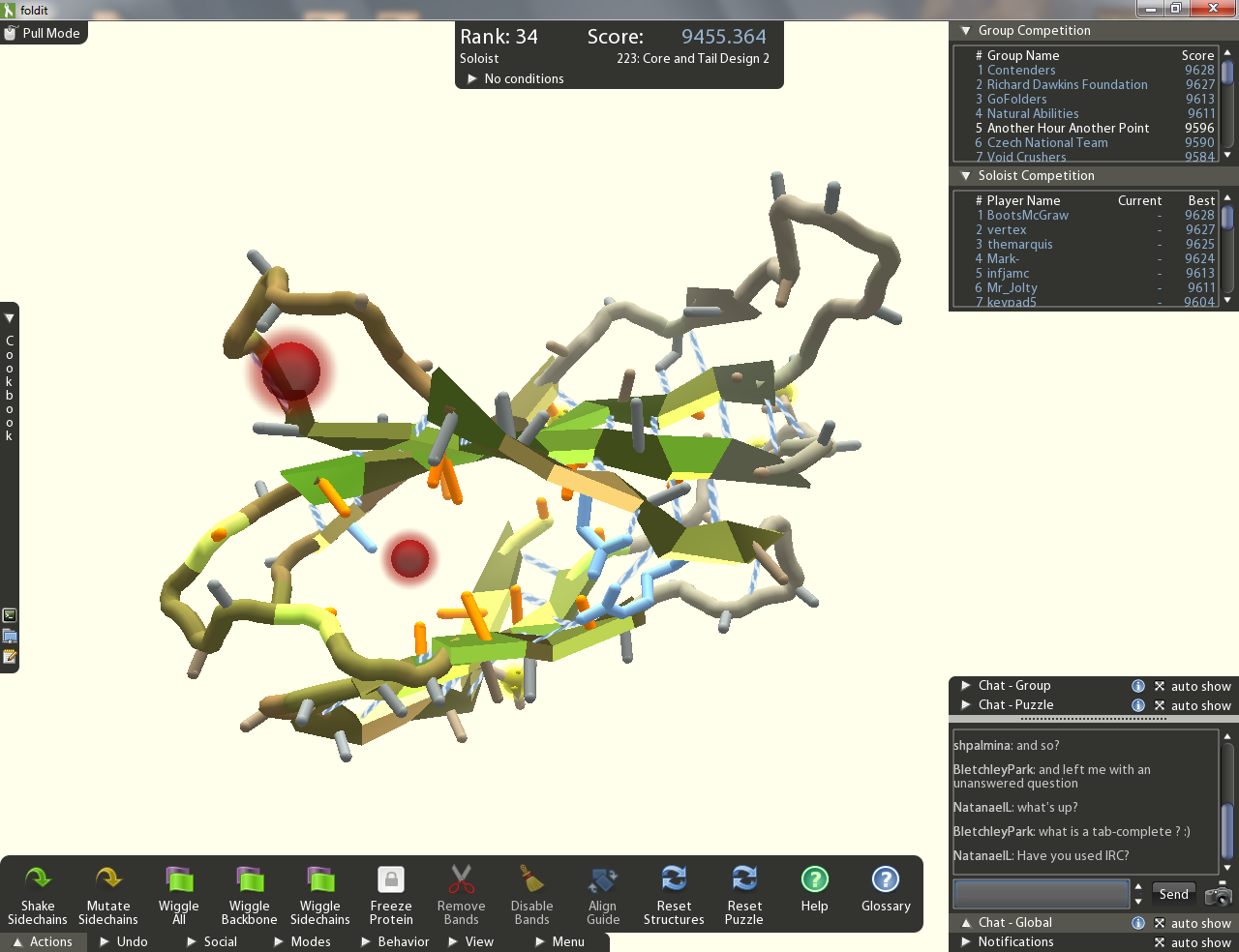

I studied citizen science using games some time ago. In particular, I focused on FoldIt, one of the most fascinating and successful projects in citizen science. It really produced breakthrough results that were published in Nature. The developers of the game made it very clear from the beginning that their tasks were not for everyone, they need people with spatial orientation and pattern recognition, problem-solving and creativity skills. Some people do not have these skills. The most successful FoldIt players do have all these skills and are extremely proud of their achievements. This is not about the democratization of science. FoldIt and similar projects represent the productivity view of citizen science, enrolling people to perform tasks researchers are not able to do alone

Can citizen science represent a way to make science actually more open, participatory? Can it offer citizens the tools to shape the political and scientific agenda and produce real changes? These themes are certainly food for thought for our community. To conclude this conversation and give a final message, indicate a path, what could you say?

It is not easy to sum up this issue, because citizen science projects have very different types of goals, involving very different people. When we take a look at the variety of citizen science projects, their aims, and who they target, we will find huge differences. Extreme citizen science had nothing to do with projects similar to FoldIt, they don’t even use the same language, just to make an example. As a researcher, I am hesitant in using a generalized statement describing citizen science as being a way to democratize science. So, my last words are: it depends!

(FoldIt image: "Foldit screenshot.png" by Animation Research Labs, University of Washington is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)